Recollections of the Past 30 years pursuing Coelacanths

Jerome Hamlin, creator dinofish.com

When we returned to New York at Christmas, 1986, our expedition was considered a great success. The frozen coelacanths went to a freezer at New York Aquarium, which also dispatched a large fish transporter to the Comoros. I focused on refining the plan for the beginning of capture expeditions aiming at the following fall. I contacted the Lowrance sonar company and they agreed to loan us two of their top of the line X-16 units. Peter would arrange the modern fishing gear to bring the fish up in twenty minutes or less. The plan called for a series of fishing visits by fishing persons until a specimen was caught and resubmerged in a cage. At that time experienced personnel would leave from New York Aquarium to maintain and return the fish in the transporter. This would indefinitely expand the capture opportunities without tying down expensive aquarium experts. To make it work I needed a series of volunteer fishers who could go to the Comoros over the next year. I put a notice in an Explorers Club publication, and Paul came up with the idea to put an ad in a magazine called International Angler. I approved, but without checking the copy he wrote. This turned out to be one of the biggest mistakes of the project, and would come back to haunt me with devastating effect. Seen out of context, it looked as though we were promoting coelacanth sport fishing in the Comoros (!), whereas in fact, it was to extend the effectiveness of the capture expedition over a period of months or even years, like follow up Apollo missions to the moon.

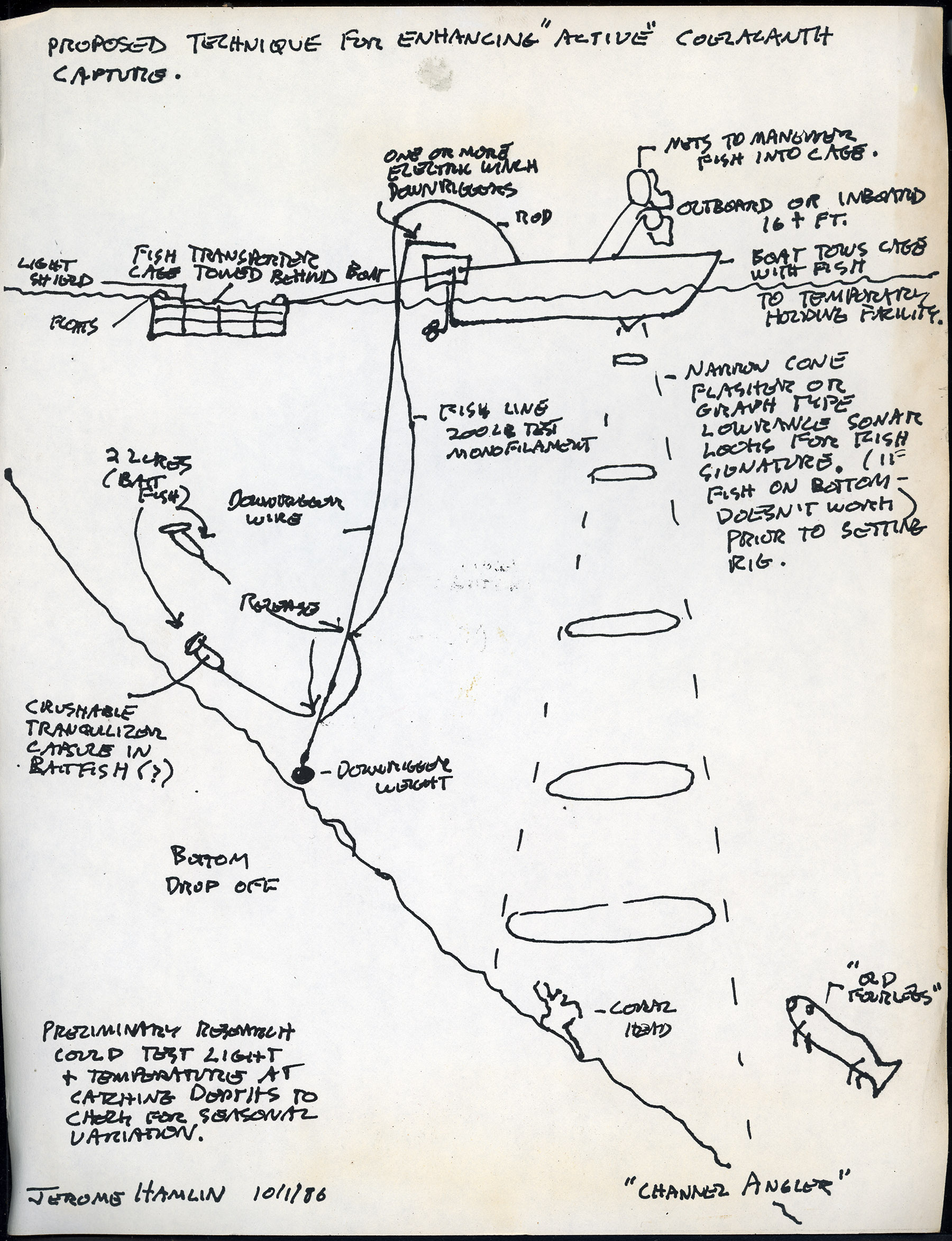

A sketch of how the active fishing would look using sonar.

We would also have to raise money for the capture expedition. That meant I would have to go for support level three at the Explorers Club. Level three would allow me to use the Explorers Club’s name in fund raising, but it was also a vey high bar to reach.

Logo I designed for our early Coelacanth Expeditions, depicting a coelacanth swimming through an Omega- representing Eternity.

The first proposal was rejected by the board of directors of the Explorers Club. One of the criticisms was that it was “showboating.” I met with the President of the Club and was told I should minimize Paul’s role in the project. Paul was active in the higher echelons of the club, and there was politics involved. As it turned out, Paul decided not to be part of the capture expedition. I turned now to our scientific advisors, the scientists who would receive the specimens from the reconnaissance trip. They prepared a robust scientific and conservation component to be coupled with the success of a live capture. The success of our project would be a scientific research and conservation bonanza. The revised proposal passed the board of directors and I had the green light to use the Club’s name in fund raising. The first thing I did was to create the beautiful stationary and t-shirts with the logo of our project now named Channel Angler- for the Mozambique Channel- the only known home of living coelacanths.

The Comorian Embassy in New York offered its full support. The coelacanth brought back would be an ambassador like the pandas from China. We allocated the returned frozen specimens to two scientific institutions in the U.S.: the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences under custody of Dr Jack Musick, and The University of Massachusetts at Amhurst, under custody of Dr William Bemis. Another fish had previously been diverted to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto where it went on display in a freezer with a transparent lid.

We waited to hear the results of the German/French submersible visit to the Comoros. Their success was confirmed when the first picture of a coelacanth swimming at its natural depth appeared on the cover of the science magazine Nature, and the front page of the New York Times! This publicity actually helped our project get some private foundation backing before our departure.

A photo of a coelacanth swimming at depth appeared in the

New York Times. 1987

Everything was set. The Comorian ambassador in New York promised red carpet treatment and two boats for our use. Two Aquarium personnel and a marine biologist Phd student would accompany us on the first capture trip. However, the magazine ad and Explorers Club appeal had produced only one volunteer and she was a SCUBA diver rather than a fishing person. How we would do follow up trips was now an open question. The Expedition was awarded Explorers Club Flag #6, the very same flag Roy Chapman Andrews had taken to the Gobi in the 1920’s, when dinosaur eggs were discovered at the Flaming Cliffs. How appropriate was that? (This flag has since been retired.) With all our equipment packed in crates and cases ready to go, I remember walking down Park Avenue in NYC on the night before departure. The building tops were gleaming in their floodlights, like Mayan temples in a sound and light show. A great adventure seemed ready to unfold. On November 18th, 1987, I left New York with the others, on my second journey to the Comoros.